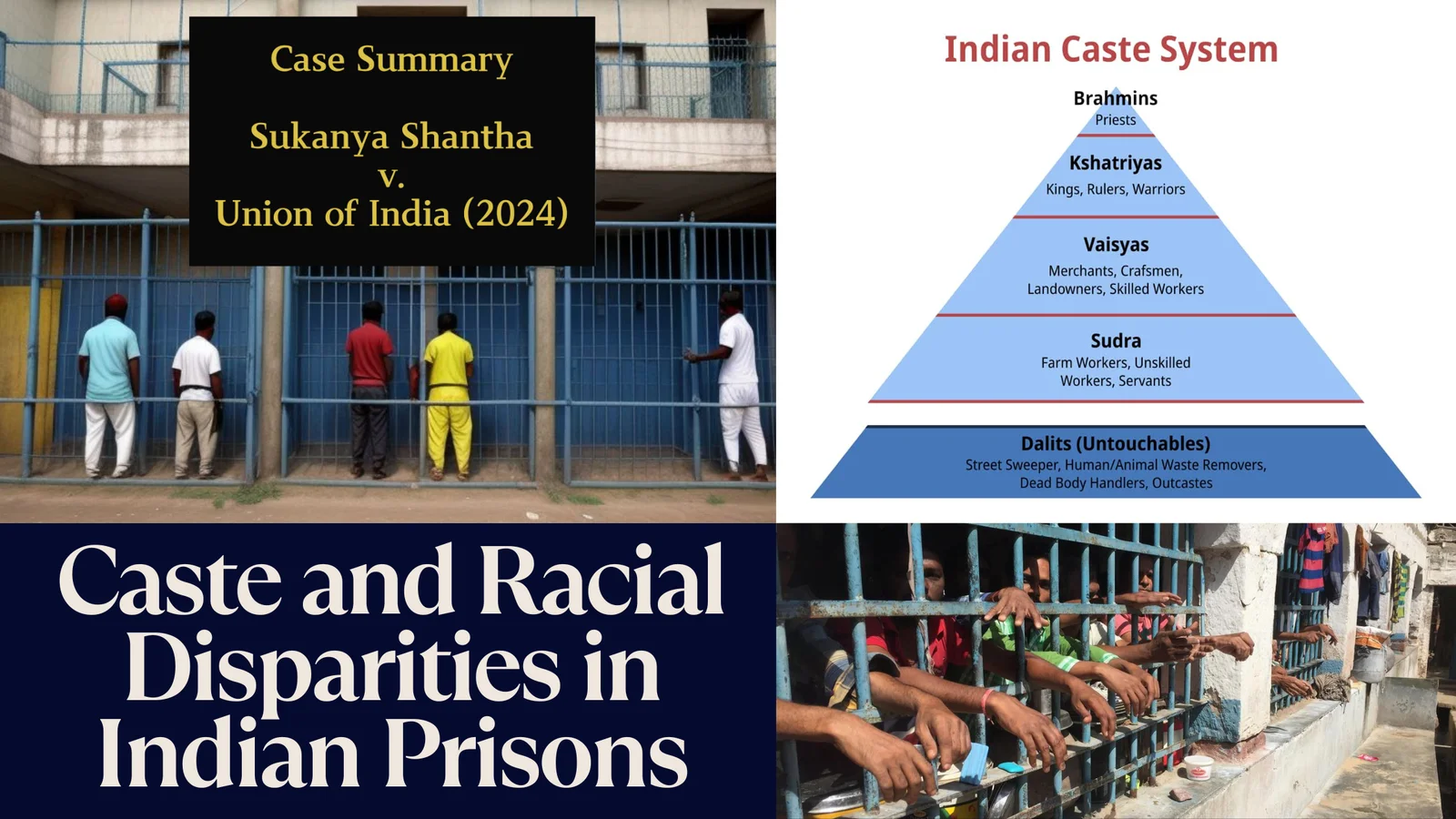

Caste and Racial Disparities in Indian Prisons

Oct. 12, 2025 • Tania Kukreja, LL.M. Student, Amity University, Mohali, Punjab

Introduction:

In 2021, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported that the Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC) has made up two-thirds of India’s prison population, despite having lower proportion in the general population. Caste and racial biases have been deep- rooted issues for centuries, leading to unfair policing, discrimination in the judicial system, and inhumane treatment in the prisons, making it clear that disparities within India’s criminal justice system are an uncomfortable reality we must face.

In the past, the marginalized communities have faced social and economic disadvantages that had pushed them into vulnerable situations, increasing their likelihood of criminalization. When arrested, they don’t have the means to economically to get access to legal representation, leading to prolonged incarceration, harsher sentences and a higher likelihood to wrongful convictions. The prison system, instead of being a rehabilitative space, mirrors the same caste-based hierarchies that exist outside its walls.

This article examines contemporary data, explores the historical context while also highlighting the systemic issues that sustain these disparities and drawing connections to similar patterns observed globally.

Historical and Legal Context:

The roots of caste-based discrimination in Indian prisons trace back to the colonial era, notably with the enforcement of the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. The British Colonial Government under this act labelled Denotified Tribes as “criminal tribes” and till today they are referred to as “habitual offenders” by the prison manuals. This enforces inherent biases and notions of ‘group criminality’ in the criminal justice system which ultimately violates the principles of natural justice and modern criminal law concepts, which view the criminality as an individual concept and not as a group concept.

Post-independence, while the Indian Constitution abolished "untouchability" and prohibited caste-based discrimination under Articles 15 and 17, remnants of these colonial practices persisted, influencing prison administration and inmate treatment.

Present-Day Realities in Indian Prisons:

Despite constitutional safeguards, caste-based discrimination remains prevalent in Indian prisons. The historical divide between upper and lower castes continues to influence prison life, often determining the privileges and treatment inmates receive. A stark example of caste-based segregation is evident in Tamil Nadu’s Palayamkottai Central Jail, where prisoners from different communities are allotted separate sections to prevent caste rivalries.

To address these issues, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) introduced the Model Prison Manual, 2016 to standardize and modernize prison management across the country. However, many state prison manuals still retain discriminatory provisions, perpetuating caste-based practices that undermine constitutional rights. These outdated rules violate fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 15, 17, 21, and 23 of the Indian Constitution, which ensure equality, prohibit untouchability, and protect the right to life and dignity.

For instance, The Rajasthan Prison Rules, 1951 explicitly assign work based on their caste. Upper-caste prisoners are designated for tasks like cooking and medical care, while inmates from lower castes are relegated to cleaning and sweeping.

Similarly, the Uttar Pradesh Prison Rules categorize individuals from the Mehtar Shreni, a caste traditionally associated with manual scavenging, as the "scavenger class." These practices reflect systemic discrimination within state prison systems, despite constitutional prohibitions.

A significant step toward addressing these issues emerged through a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed in the Supreme Court — Sukanya Shantha v. Union of India (2024). This PIL called for the elimination of caste-based discrimination, segregation of prisoners, and the revision of discriminatory provisions targeting Denotified Tribes. The case was initiated following a journalistic Report by Sukanya Shantha, which exposed the persistent caste-based biases in Indian prisons.

While the Model Prison Manual emphasizes fair and consistent treatment of inmates, its implementation remains inadequate. Marginalized communities often face forced assignments to cleaning and manual scavenging tasks, while prisoners from upper castes are entrusted with more privileged roles like cooking. This institutionalized segregation amounts to state-sanctioned discrimination. Despite the legal abolition of manual scavenging, it continues to thrive within the prison system, further entrenching caste-based hierarchies.

Comparison Between Indian and U.S. Prisons:

Both India and US encompass systemic disparities in their prison systems. In India, marginalized castes are disproportionately represented in prisons, reflecting deep-seated social stratification. As per the report of “United Nations on Racial Disparities in the US Criminal Justice System”, similarly in the United States, African Americans and Latinos face higher incarceration rates compared to their white counterparts.

In India, there is caste-based discrimination in the prisons which determines the prison labor and privileges, while in the U.S., racial profiling and sentencing disparities disproportionately affect the African-American and Latino communities.

Both the communities in their respective countries face limited access to legal representation. While the U.S. has introduced measures like the First Step Act for prison reform, India still lacks comprehensive national policies to address caste-based prison discrimination, leaving reforms largely to state discretion.

Proposed Reforms

Following the Supreme Court's decision, several reforms have been proposed to eradicate caste-based discrimination in prisons:

- Revision of Prison Manuals: States are directed to amend outdated provisions that perpetuate caste-based labor and segregation.

- Sensitization Programs: Implementing training for prison staff to promote equality and prevent discriminatory practices.

- Monitoring Mechanisms: Establishing oversight committees to ensure compliance with anti-discriminatory policies and uphold inmates' rights.

Conclusion

As Dr. B.R. Ambedkar emphasized, achieving social democracy is as essential as attaining political democracy. The denial of equality and dignity in Indian prisons weakens the fabric of social democracy and poses a threat to political democracy. True justice can only be realized when we confront and dismantle entrenched biases that perpetuate inequality, ensuring a more just and inclusive society for all.

References:

3- IACL-AIDC